Alchemy in Medieval Literature

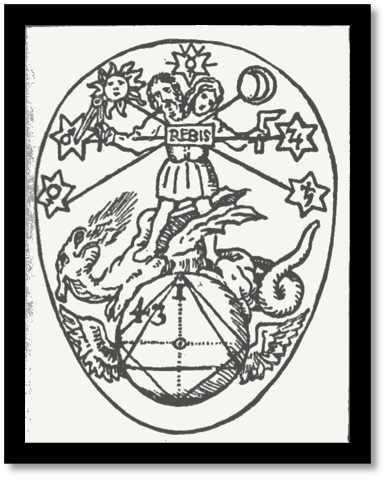

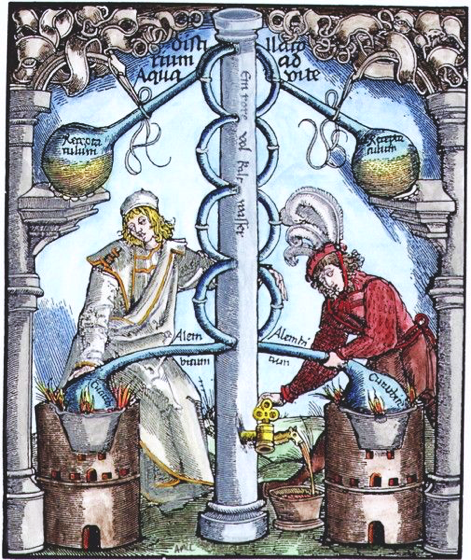

The alchemist of the Middle Ages was usually a professed Christian, often a monk or clergyman, who studied what he could of Hermetic alchemy, Greek philosophy, the Jewish Kabbalah, and his own native and foreign magic. The Great Work of the alchemist, in emulation of the “Great Architect,” was to unite the divine opposites, macrocosm and microcosm, to produce a unified and balanced whole.

The macrocosm was the exterior world, the heavens of astrology and the four material elements: fire, water, air, and earth. The microcosm was the spirit embedded within the elements. The alchemist represented Mercury, the union of divine opposites as Sun and Moon, a symbolism that appears prominently on the Masonic First Degree Tracing Board. To this day the Master Mason identifies with Mercury.

In 1317 Pope John XXII issued the Bull “Spondent quas non exhibent” banning alchemy. In 1403 the English King Henry IV had banned the practice of alchemy without a license, granting licenses to those trustworthy enough to attempt to actually make gold. The literature of the Middle Ages reveals the general perception and prejudice surrounding the alchemist at the time.

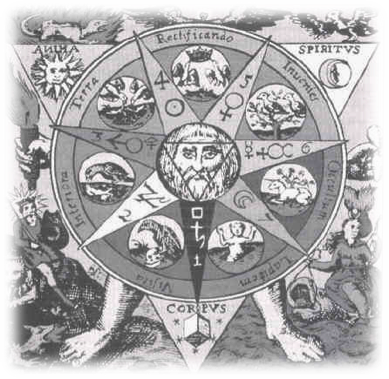

V.I.T.R.I.O.L., Basil Valentine

The Italian Dante (c. 1265 – 1321), recognized as one of history’s greatest poets, is best known for his Comedìa, or the Divine Comedy. The work is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. The Inferno describes the nine circles of Hell, which tunnel deeper to the center, wherein resides the devil. The circles of Hell are Limbo, Lust, Gluttony, Greed, Wrath, Heresy, Violence, Fraud and Treachery.

In canto 29, Dante describes the eighth circle of Hell, the hell reserved for those who commit fraud, including panderers, seducers and flatterers, grafters, hypocrites, thieves, corrupt churchmen and politicians, and imposters. Also belonging to this hell are astrologers, fortunetellers, false prophets, magicians and alchemists. Dante visits the spirits of two historical alchemists, Griffolino d’Arezzo and Capocchio, who were burnt at the stake for practicing alchemy. Griffolino was executed by the Bishop of Sienna for defrauding Alberto da Siena out of monies on the pretense of teaching him to fly. Dante may have known Capocchio personally, who was condemned to death in 1293 for producing imitations of precious metals.

Dante’s “Inferno,” from The Divine Comedy

Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343 – 1400), the Father of English literature and greatest English poet of the period, is best known for his The Canterbury Tales, a collection of short stories told from the perspective of various archetypal characters on a pilgrimage. In “The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale” the Canon’s Yeoman exposes the Canon as an alchemist, which causes the Canon to run away in shame. The Yeoman then tells the Canon’s story. According to the Yeoman, the Canon sought after the Philosopher’s Stone and made imitation gold in the meantime. The Canon’s futile quest and deceptive alchemy left him in poverty and burdened with lead poisoning.

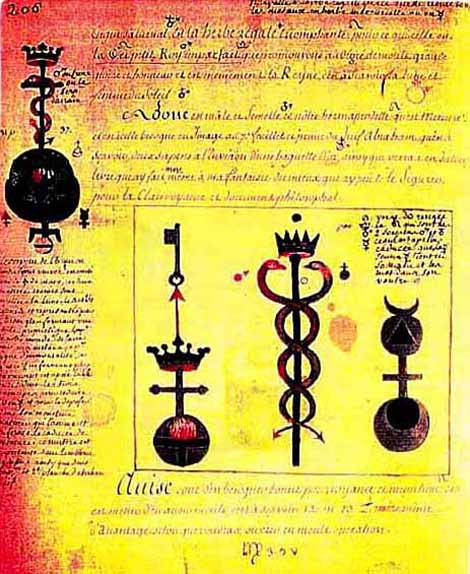

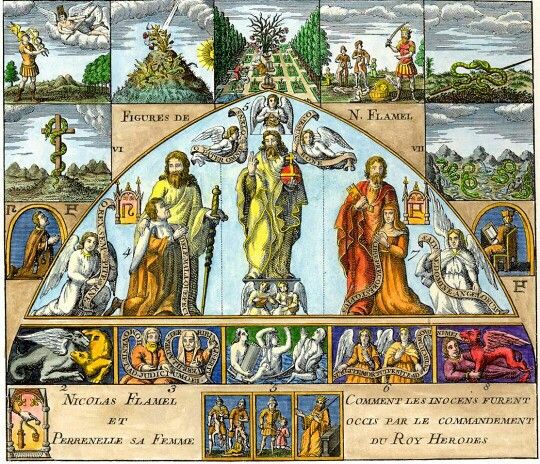

Alchemical Illustration, Nicholas Flamel

The tale may have been inspired by a canon named William Shuchirch at King’s Chapel, Windsor, who may have come into contact with Chaucer when the latter facilitated the repair of the chapel in 1390. In 1374 Shuchirch had been named as the alchemy teacher of the chaplain William de Brumley, who confessed to producing fake gold. A long tradition, subscribed to by the likes of Elias Ashmole, maintained that Chaucer, himself, was an alchemist. A later theory speculated that the poet may have been swindled by Shuchirch or another false alchemist, which drove him to write so derisively of the practice.[1]

Chaucer probably derived his own technical knowledge of alchemy from Speculum naturale (Mirror of Nature), the primary encyclopedia of natural history and science at the time, by Vincent of Beauvais (c. 1190 – c. 1264). Chaucer mentions Arnold of Villanova (c. 1240 – 1311), to whom were falsely credited the alchemical works Rosarius philosophorum (Rosebush of the Philosophers), Novum lumen (New Light) and Flos florum (Flower Among Flowers). Chaucer may also have been familiar with works attributed to Raymon Lull and any number of other alchemists.

“The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale,” The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

[1] Correal, Robert M., Ed., Sources and Analogues of the Canterbury Tales, Volume II, D. S. Brewer, Cambridge, 2005, pp. 716 – 718.

William Langland (c. 1332 – c. 1386) was the famous author of Piers Plowman, one of the greatest works of English literature in the Middle Ages, alongside Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and the Pearl Poet’s Authurian chivalric romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. His characterization of the common view of alchemy is comparable to Dante’s and Chaucer’s.

Dame Studie’s speech in Passus X describes the common distrust of geometry and the natural sciences, that is, ways of knowledge independent of religious faith. They are dangerous, too, because they are difficult subjects that may lead a non-expert astray into more occult, magical or fraudulent studies. Geomancy (divination), sorcery and alchemy are crafts to be avoided. She also expresses dislike for the art of rhetoric as a means of persuasion without concern for the truth. Theology is touted as the paramount education.

“Ac astronomye is an hard thyng,

And yvel for to knowe;

Geometrie and geomesie,

So gynful of speche,

“Who so thynketh werche with tho two

Thryveth ful late,

For sorcerie is the sovereyn book

That to tho sciences bilongeth.

“Yet ar ther fibicches in forceres

Of fele mennes makyng,

Experimentz of alkenamye

The peple to deceyve;

If thow thynke to do-wel,

Deel therwith nevere.

“Alle thise sciences I myself

Sotilede and ordeynede,

And founded hem formest

Folk to deceyve.”

The Vision of Piers Plowman by William Langland

Benjamin “Ben” Jonson (1572 – c. 1637) was the most important playwrite of his time after William Shakespeare. He is known for several plays, including his best-received comedy, The Alchemist (1610). The play follows three companions, two conmen and a prostitute, who claim powers of necromancy and alchemy to defraud victims out of their wealth. The folly of vanity saturates the play’s characters and alchemy is presented as the epitome of this foolishness. Jonson satirizes greed with the quest for the philosopher’s stone that turns base metals into gold, and lust with the pursuit of the elixir of youth.

It is interesting that alchemy appears in the entertainment of the Middle Ages only as an operative practice inspired by greed, lust, desire for immortality, or worse yet, as a form of fraud taking advantage of these weaknesses in others. This certainly is part of the story of alchemy; the dark side, it might be said. However, the valuable scientific and spiritual aspects of alchemy too, are borne out in the history of its greatest practitioners from ancient times to the present day. A good portion of these enlightened alchemists lived in the Middle Ages. Some were doctors, some were scientists, and many held high office in church or state. Their lives tell a very different story than the fictional narratives of Dante, Chaucer, Langland and Jonson.

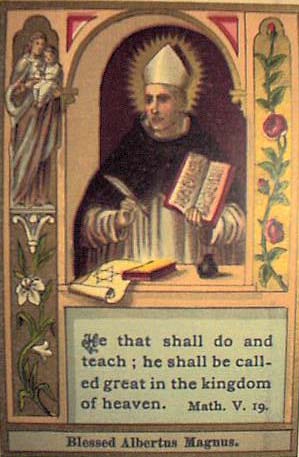

Albertus Magnus, Patron Saint of the Natural Sciences

Albertus Magnus

The Bavarian-born Albert of Cologne (1193 – 1280 CE) was the German Provincial Superior of the Dominican Order, a bishop, a Roman Catholic patron saint of the sciences and Doctor of the Church. Fellow alchemists such as Roger Bacon referred to him as Albertus Magnus (“the Great”) in reference to his achievements. Albertus was a thorough preservationist and investigator of the works of Aristotle. He wrote commentaries on most of the works of Aristotle and was well versed in Muslim scholarship. He did his own scientific experiments and made his own mathematic and logical observations. He argued for the peaceful co-existence of religion and science.

Albertus Magnus wrote on a variety of subjects, including law, philosophy, theology, astrology, music, logic, alchemy, and several branches of science. Due to his reputation his name was used by many anonymous authors as a pseudonym, so many alchemical works have been falsely attributed to him. Albertus taught that truth was not to be found by appeal to authority, but rather through personal investigation into nature. He promoted an empiricist program of gathering scientific evidence rather than human reasoning without direct experience.

Albertus was a teacher of Thomas Aquinas, who also labored to join science and religion and became a Catholic saint. He was a favorite subject of Dante and later alchemists and magicians, who made a legend of him and assigned alchemical works to his authorship. Albertus Magnus is remembered as the first prominent European alchemist of this era.

Triumph of St Thomas Aquinas, “Doctor Communis,” between Plato and Aristotle,

Benozzo Gozzoli, 1471. Louvre, Paris

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274 CE) was an Italian mystic, Dominican friar and Catholic priest. In the sixteenth century was recognized as a Doctor of the Church, that is, a great saint and teacher of Catholic doctrine. He was a Scholastic philosopher, theologian and jurist, who based many of his ideas on Aristotle and the Neo-Platonist Pseudo-Dionysus. He was a student of the alchemist Albertus Magnus, and his thoughts on elements and compounds influenced future thinkers like Duns Scotus and William of Ockham. Aquinas was a professor of theology and taught in Italy and France.

Aquinas became the principal philosopher of natural theology and founded the school known as Thomism, known by the Second Vatican Council as “the Perennial Philosophy.” Aquinas relied heavily on Aristotle and is notable for his attempt to reconcile Aristotle’s natural science with Christian theology. It must be noted that in true medieval form he was fiercely loyal to the Church, certainly not an objective thinker, but what today would be red flagged as a religious extremist. Aquinas held that heretics should be severed from the Church with excommunication and severed from life with execution (Summa Theologiae, II–II, Question 11, Art. 3).

Aquinas had faith that the Bible was the word of God and considered theology a branch of science. He believed in miracles and visions. He imagined that there exists a soul that survives the death of the body and is rewarded or punished in the afterlife. Aquinas also believed in the Biblical resurrection of the dead. However, he argued against the common view that divine revelation was the only way to knowledge, insisting that knowledge could be attained through observation with the senses and reason. The Catholic Church regards Aquinas as a great saint, teacher and role model for priests. He is the embodiment of the Catholic theologian and rational intellectual.

Aquinas’ primary works are the Summa Theologiae and the Summa contra Gentiles, as well as his commentaries on Aristotle and on the Bible. His beautiful and timeless Eucharistic hymns, like the prayer “Adoro Te Devote,” are used in liturgy to the present day. By tradition, Aquinas’ last book was a treatise on alchemy called Aurora consurgens (“Rising Dawn“), discovered by Dr. Carl G. Jung, but it is now assigned to a “Pseudo-Aquinas.”

Although Aquinas’ philosophy is important in the history of reason and science, in his vast writings, he only briefly touched upon alchemy. Aquinas believed in the “excellence and purity” of the substances of silver and gold, in addition to their natural uses, and asserted that an alchemist who sells imitation silver or gold is commiting fraud on both these counts.

The properties of gold according to Aquinas are that it makes people joyful, it is medicinal, it may be used frequently and it lasts longer than imitation gold. He states, however, that if real gold could be produced by alchemy, then selling it as genuine would be lawful. He quotes Augustine as saying that art, even the art of demons, can naturally produce natural effects. (Summa Theologiæ II-II. Question 77. Art. 2).

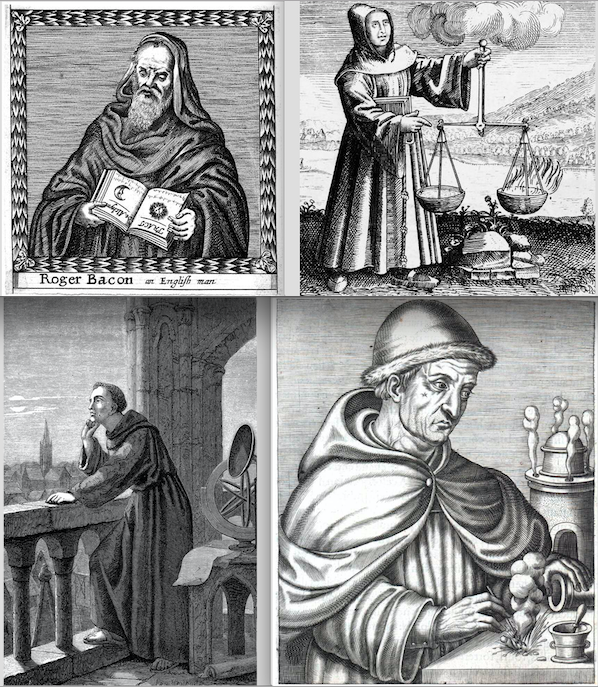

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (c. 1220 – c. 1294), known as Doctor Mirabilis (Latin: “Wonderful Teacher”), was the first practicing scientific alchemist of the European Middle Ages. He was an English Franciscan friar, theologian and empirical natural philosopher, a pioneer of scientific method. He studied Aristotle and the Bible in the scholastic tradition at the University of Paris, where he earned his Master of Arts, and at Oxford University.

Bacon recommended a thorough knowledge of Latin evolve into a general study of languages, especially the original languages of scripture. He studied the works of ancient Greek philosophers before they had been translated to Latin. He was keen to make critical assessments of translations and interpretations of scripture and Greek philosophy. Bacon recognized the importance of an education in the seven liberal arts and natural philosophy (science.) Bacon sent a copy of his Opus Majus, or Greater Work, to Pope Clement IV in 1267 as an example of how to unify Aristotelian experimental natural science with Christian theology.

Bacon’s 840 page Opus Majus included essays on the subjects of grammar, mathematics, physics, mechanics, astronomy, astrology, geography, agriculture, medicine, alchemy, philosophy, theology, philosophy of science and morality. He famously stated that “theories supplied by reason should be verified by sensory data, aided by instruments, and corroborated by trustworthy witnesses,” laying the foundation for modern empirical science. Descartes and Galileo would later place mathematical observations above sense perceptions of nature.

Bacon published the Opus Minus and Opus Tertium as introductions to his Opus Majus. He is alleged to have authored several alchemical works. He was the first European to describe the recipe for gunpowder, which he probably reverse engineered from a Chinese firecracker at his Franciscan monastery. Bacon edited his own annotated edition of the Secret of Secrets (Latin: Secretum Secretorum), also known as the Secret Book of Secrets (Arabic: Sirr al-ʿasrar) and the “Mirror of Princes.”* This book of statecraft, ethics, medicine, alchemy, astrology and magic is traced to an tenth century Arabic source but was falsely packaged as a letter of Aristotle to Alexander the Great.

The Letter on the Secret Workings of Art and of Nature and on the Vanity of Magic (to William of Paris) attributed to Bacon includes alchemical methods for producing silver and gold. It recommends maintaining perfect health and using certain secret minerals and herbs for longevity. The letter endorses the Book of Secrets and other works of Aristotle, as well as Pliny’s Natural History, the mathematics of Ptolemy, and experimentation.

The Mirror of Alchimy, falsely ascribed to Roger Bacon, was published in Latin as Speculum Alchemiae in the first European alchemical anthology, Johannes Petreius’ 1541 De alchimia. It was published again in Latin in 1602 in the important Theatrum Chemicum. George Ripley’s The Compound of Alchymy, printed in 1591, was the first-ever English book of alchemy. The Mirror of Alchimy was the second, translated into English in 1597.

The Wikipedia article on Roger Bacon has a wealth of information and original sources.

[*] Not to be confused with The Book of Secrets (Arabic: Kitab al-Asrar; Latin: Liber Secretorum) by the famous alchemist Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi.

Mercury and Sulfur

Pseudo-Geber

All that is known of the author that wrote under the pseudonym “Geber” is that he was a Spanish alchemist and metallurgist who wrote at the end of the thirteenth century. Today he is known as the Latin Pseudo-Geber, author of The Height of Perfection of Mastery (Latin: Summa perfectionis magisterii) and other alchemical works. “Geber” is the Latinized name of the prominent ninth century Muslim alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān.

William R. Newman’s 1991 The Summa Perfectionis of Pseudo-Geber: A Critical Edition, Translation, and Study, posits the theory that Paul of Taranto, a thirteenth century Italian Fransiscan monk, was author of the Summa perfectionis. Paul of Taranto was the author of the alchemical Theory and Practice (Latin: Theorica et practica), where he defends the theory that sulfur and mercury are the two basic substances that form all metals.

The sulfur and mercury theory inaccurately predicts that the particular proportions of these two materials are what distinguish different metals. According to this model, it should be possible to reduce any metal to the four elements and recreate any metal using alchemical processes. An elixir was supposed to have the power of transmuting base metal into gold.

Pseudo-Geber was an early experimenter in the production of mineral acids. His discovery of sulfuric acid was a profound step in the science of chemistry. He quickly gained renown among European alchemists, especially with the Summa perfectionis, which opened up the secretive and perplexing world of alchemy with well-defined proto-scientific theories and laboratory instructions.

Hortulanus

Hortulanus (“Gardener”) or Ortolanus was an early fourteenth century alchemist about which very little is known. He was the author of the Liber super textum Hermetis. His book is the first to associate the quintessence with alcohol. The first part of the text, a practical manual, proposes that quintessence, the essence of all things, may be most readily distilled from several substances, especially wine. This first section was left unpublished and was generally unknown.

The second part of the text is a commentary upon the Emerald Tablet of Hermes devoted to interpretation and theory. Hortulanus divides the universe into spirit and matter, identifying the quintessence as the spirit, which originates and animates the cosmos out of primeval chaos. This spirit would later be associated with mercury and the Holy Spirit by later alchemists. The Emerald Tablet was conceived as a formula for the Philosopher’s Stone hidden in symbols and allegory. This commentary was published several times in the sixteenth century and became a well established authority in alchemical matters.

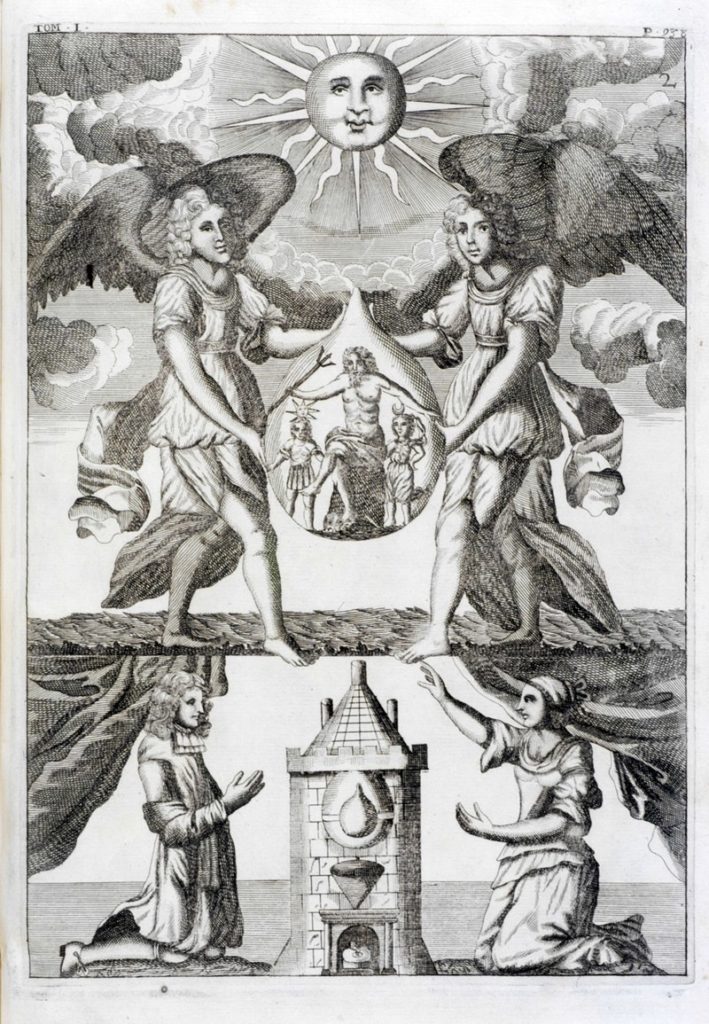

Liber super textum Hermetis or “Commentary on the emerald tablet of Hermes.”

Figure 2, Volume 1, Bibliotheca chemica curiosa, Jean-Jacques Manget, 1702

John Dastin

John Dastin (c.1293 – c. 1386) was an English vicar and alchemist from Gloucestershire who studied at Oxford and worked in England, France and Italy. In 1317 Pope John XXII issued an edict banning alchemy, the Bull “Spondent quas non exhibent.” Dastin defended alchemy in a letter to Pope John XXII in 1320, arguing that there was no significant difference between naturally occuring gold and manmade gold prepared by transmutation of another metal.

Dastin’s alchemical writings appeared in the 1625 Harmoniae imperscrutabilis Chymico-Philosophicae by Hermannus Condeesyanus and the 1629 Fasciculus chemicus by Arthur Dee (1579 – 1651), the son of Queen Elizabeth I of England’s official Royal Advisor on Mystical Secrets, John Dee. Arthur was an alchemist who served as physican to Tsar Michael I of Russia and King Charles I of England. Dastin wrote the initially obscure Visio Edwardi, which was published in 1625 as the Visio Ioannis Dastin and translated to English in 1652 as Dastin’s Dreame in the famous Theatrum chemicum Britannicum of Elias Ashmole.

The Rosarius philosophorum, also known as the Desiderabile desiderium (English: The Desired Desire), may have been written by John Dastin. It was printed in the Bibliotheca chemica curiosa (English: Curious Chemical Library) of Jean-Jacques Manget in 1702. Jean-Jacques Manget, or Johann Jacob Mangetus (1652 – 1742), a Genevan physician and early epidemiologist, wrote and compiled works on medicine and alchemy. The Rosarius may have been written by Arnaldus de Villa Nova (1238 – 1311) as La Vraie Pratique de la noble science d’alchimie. It was also attributed to Nicolas Flamel and called The Book of Washing.

Raymond Lull

Ramon Llull, (c. 1232 – c. 1315), Anglicized as Raymond Lull or Lully, was a philosopher, logician, and author. Ramon Llull was born in Palma, the capital of the kingdom of Majorca, founded by James I of Aragon after the land was taken from Muslim control. It was Llull’s lifelong goal to unite Jews, Christians and Muslims with reason, and convert everyone to Christianity using logic. He believed Christianity was the rational end result of comprehensive philosophical reasoning.

Llull’s career advanced from tutor to James II of Aragon, who would become king of Aragon and Valencia, king of Sicily and king of Majorca, to Seneschal, steward of the royal household, to the future King James II of Majorca. Raymond was married, had two children and was a troubadour until he had a series of visions of Christ on the Cross, whereupon he became a Franciscan tertiary, a member of the Third Order of Saint Francis, the secular branch of the order that includes both men and women, often married, living worldly lives.

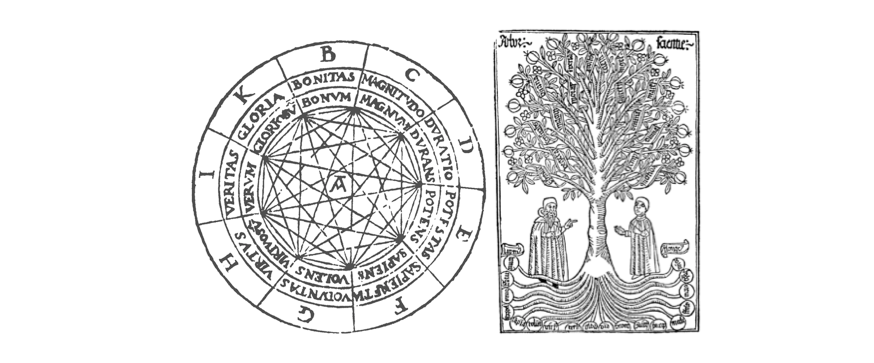

Llull cultivated a view based more on Neo-Platonism than the scholasticism and was the first Christian to study Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition. He considered astrology to be a worthy science. While Llull was not an alchemist and spoke against alchemy, his name was attached to what would become respected alchemical and esoteric works.

Llull studied Latin and Arabic, Christian and Islamic theologies, and culture. Believing that he could convert Muslims to Christianity with logic, Llull devised a system he called the Art, complete with charts and visual aids, to assist conversion attempts. The theory was that by combining the basic elements of knowledge one could collect all information. The Art would later influence sixteenth century philosopher Giordano Bruno and seventeenth century mathematician Gottfried Leibniz.

Llull visited royalty, ecclesiastics and academics all over Europe to promote Christian missionary work over forced conversion. He repeatedly did his own missionary work in North Africa. In his eighties Llull was in North Africa when an angry mob of Muslims stoned him. He returned home to Palma and died of his injuries, becoming a martyr. Pope Pius IX beatified Raymond Lull in 1847.

Nicolas Flamel

Nicolas Flamel (1330 – 1418) was a Parisian bookseller and scribe. He and his wife were a wealthy French Catholic couple and there is no evidence that either of them were involved with alchemy. In 1561 “The Philosophical Summary” attributed to Nicolas Flamel was published as “Le Sommaire philosophique” in De la transformation metallique, by Guillaume Guillard and Amaury Warancore (pp. 97 – 120).

In 1612 a book entitled Livre des figures hiéroglyphiques, or Exposition of the Hieroglyphical Figures, was published and falsely attributed to Flamel. This book claimed that Flamel had purchased the Book of Abramelin the Mage and from it he and his wife had been able to successfully produce the Philosopher’s Stone. Thus, the legend began, and at least four other alchemical works were later attributed to Nicolas Flamel.

The legend of Flamel the alchemist gained popularity over the centuries and he appeared in the works of Isaac Newton, Victor Hugo, Albert Pike, Dan Brown and J.K. Rowling, among others. The earliest known version of the Book of Abramelin the Mage is dated 1608. It is a German book of magic and Kabbalah of unknown origin. The book was a central influence in the nineteenth-twentieth century magical societies the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (G.’.D.’.), Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) and the Astrum Argenteum (A.’.A.’.).

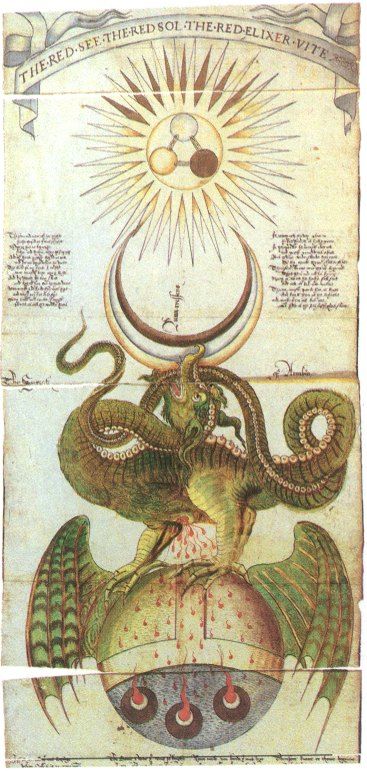

Lindorm Dragon Detail from a Ripley Scroll

Sir George Ripley

Sir George Ripley (c. 1415 – 1490) was an Augustinian canon of Bridlington Priory and Cathedral in Yorkshire, England, as well as an alchemist and author on alchemy, writing mostly in verse. He practiced speculative (symbolic) as well as operative alchemy, viewing the craft as a path of mystical ascent from base existence to the divine father, characterized as Phoebus (Apollo, Greek god of the sun) or a (presumably Christian) monotheistic God. Ripley lived his final years as an anchorite in Yorkshire.

Ripley was influenced mainly by the writings of a pseudo-Ramon Lull and was familiar with alchemical works from the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus to the work of Roger Bacon. He in turn was an influence on alchemists through the centuries, including John Dee, Robert Boyle, Eirenaeus Philalethes, Isaac Newton and Carl Gustav Jung. His major work, The Compound of Alchymy, also known as the Twelve Gates Leading to the Discovery of the Philosopher’s Stone, was published in 1471 with a dedication to King Edward IV. The Twelve Gates are:

The First Gate – Calcination

The Second Gate – Solution

The Third Gate – Separation

The Fourth Gate – Conjunction

The Fifth Gate – Putrefaction

The Sixth Gate – Congelation

The Seventh Gate – Cibation

The Eighth Gate – Sublimation

The Ninth Gate – Fermentation

The Tenth Gate – Exaltation

The Eleventh Gate – Multiplication

The Twelfth Gate – Projection

Ripley’s alchemical poem Cantilena Riplaei was the inspiration for a famous fifteenth century illustrated scroll depicting an alchemical preparation of the Philosopher’s Stone. Over the next two hundred years copies of the scroll were produced, some versions including verses from the poem, and the artwork became known as the Ripley Scroll. Twenty-three versions exist in various locations around Britain, France and America.

The complete Yale University version of the Ripley Scroll

Azoth Emblem of Basil Valentine

Basil Valentine

The legendary Basilius Valentinus was purportedly a prolific fifteenth century German alchemist and Canon of the Benedictine Priory of Saint Peter in Erfurt, Germany. Due to lack of any evidence of his life, he may be a legend invented after the publication of the books attributed to him. His works have been found to be the product of several authors, all unknown except a German salt manufacturer named Johann Thölde, who was probably the first.

Numerous publications on alchemy in Latin and German were published under the name Basil Valentine such as The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine (1599), The Medicine of Metals (1624), Azoth of the Philosophers (1624) and The Triumphant Chariot of Antimony (1646).

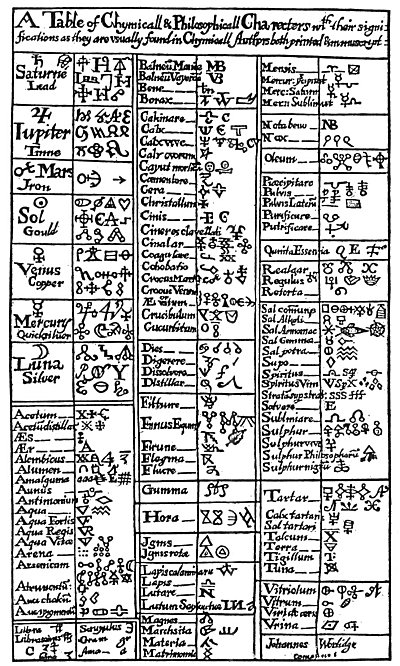

Basil Valentine’s Alchemy Table

The alchemist known as Basil Valentine was both speculative and operative. In his laboratory he produced ammonia from alkali metal (a salt that dissolves in water) and sal-ammoniac (ammonium chloride); he manufactured hydrochloric acid by acidification of the brine (water with a high concentration of salt) of common salt (sodium chloride); and he created the oil of vitriol (sulfuric acid). The latter is a speculative alchemical operation, as well, called Dissolution.

“Dissolution means to dissolve the gross elements of the alchemist, the microcosm, in the cosmos or macrocosm. In Chemistry, dissolution is the operation whereby a solid, liquid or gas forms a solution in a solvent. In alchemy Dissolution refers to the natural corrosive power of water on metal that produces rust and the oil of vitriol. It is the process of breaking down the WHITE ASH or WHITE TINCTURE, which is now symbolized as the SALT iron sulfate (green vitriol), with WATER, to produce red iron oxide (RUST) and sulfuric acid (OIL OF VITRIOL or CINNABAR). The latter two symbolize the gross elements and spirit respectively.” (The Elixir of the All-Seeing Eye of the Royal Art Society.)

It is clear that the Middle Ages was not entirely without learning and progress. The era will always be known as the “Dark Ages” due to the violent dominance of religious fanaticism over basic human rights and scientific inquiry. Still, it was the monks that primarily copied, translated and illuminated the Greek and Latin texts from ancient and Classical times in their scriptoriums and libraries.

As Christianity matured and mellowed somewhat, Christendom began to reinterpret the world and scripture in the light of humanism, scientific method and early “pagan” culture. Beginning in Italy following the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, when Greek scholars flocked to Europe, this “rebirth” became known as the Renaissance.

The Medieval Hermetic-Kabbalistic Tradition and Rosicrucianism